Main image: “The south building consisted of a workmen’s club and institute, with reading-rooms, built over two shops. It is now numbered 1 Brassey Square and 78 Sabine Road and was converted to a private house in the 1990s.”

From a Draft Chapter 12 of the Survey of London:

“Shaftesbury Park was the most assiduously publicized and widely discussed housing experiment of its day. Built between 1872 and 1877, it was the first major development of the Artizans’, Labourers’, & General Dwellings Company, founded by a band of working men in 1866-7.

The new 42½-acre estate, promoted as the ‘Workmen’s City’, was widely seen as demonstrating a credible solution to the urban housing problem. Initially the Artizans’ Company seemed to have cut the knot that tied housing reform to ‘philanthropy plus five per cent’. Through ‘industrial partnership’ and a unique financial model it could build better houses for less than the speculative builder, pay its workmen more than standard wages, sell or let its houses below the market level, and yet produce a return on capital not of five, but six per cent. It offered its inhabitants not only a healthy home environment but the benefits of community living, underpinned by cooperation and self-help.

As a suburban cottage estate, Shaftesbury Park differed in form from the creations of most model-dwellings builders at the time, with their focus on high-density exploitation of city sites. But it owed comparatively little to the British tradition of planned villages and suburbs; closer precedents were the cités ouvrières of Second Empire France…

…Shaftesbury Park faded from the wider public consciousness, and its subsequent reputation reflected the philanthropic paternalism of the reformed Artizans’ Company and not the working-class aspirations to which it owed its conception. It was mainly remembered for having no public houses…

…Shaftesbury Park was first referred to as the Workmen’s City by Lord Shaftesbury in his inaugural speech in 1872. At that date, workmen’s or workman’s city was the usual translation of cité ouvrière, a term popularized by the workers’ housing estates built in eastern France during the Second Empire. The English phrase would have been well known to the originators of Shaftesbury Park. It had been given some currency in the 1860s, by journalists and notably by the evangelical writer Charlotte Ward, who used it to describe the first and best-known of the cités ouvrières, that at Mulhouse, begun in 1853…

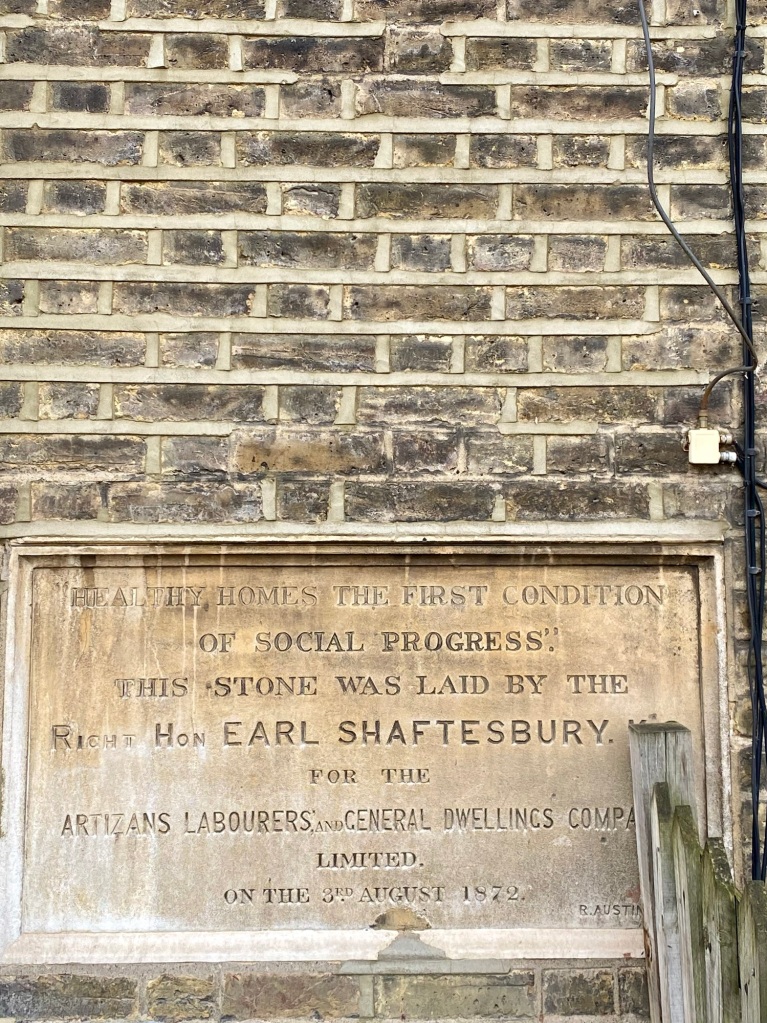

…Shaftesbury Park was formally inaugurated on 3 August 1872 (a

Saturday afternoon, to suit working men) with the laying by Lord Shaftesbury of a memorial stone at the site of what are now 65 & 67 Grayshott Road. It bears the slogan ‘Healthy homes, first condition of social progress’ (recalling the New Social Movement’s demands)…

15 July 1874, who remarked ‘Stronger than my sympathy is my surprise at what you have done. I have never in my life been more astonished.’ This was vindication for Lord Shaftesbury’s doubts about the chances of success of this ‘great experiment’, which he had secretly held on the day he laid the foundation stone two years previously. Disraeli also commented that the estate was a ‘workmen’s city rising out of the desert’, which drew the disgruntled reaction from a local newspaperman that this was ‘just the sort of exaggerated remark to be expected of people living north of the river.’” (Shaftesbury Park Estate Appraisal & Management Strategy)

…the novelty of the estate was in the overall conditions there – with their beneficial effect on sickness and mortality rates – not so much in its architectural character, in which the company had limited interest. It claimed only ‘well-arranged, honestly-built houses, such as would delight Mr. Ruskin by their thoroughness of workmanship’. But the company could draw on respected names from within the building professions for support. It was stated in 1874 that an ’eminent Architect’, Thomas Miller Rickman (actually a quantity surveyor), had been to inspect Shaftesbury Park, ‘upon which he reports in terms of high praise. He has taken 50 shares.’ Arthur Blomfield, Alfred Waterhouse and the retired Decimus Burton were also shareholders. But the pre-1877 management made no attempt to secure the services of a professional architect, though it might have made capital from the fact.

Instead, it retained Robert Austin, whom the architectural press did not deign to name in its accounts of Shaftesbury Park. However, as work got under way in late 1872 or 1873, the young, architecturally trained James George Buckle was taken on as Austin’s assistant…

…The Shaftesbury Park houses are almost all two-storey terraced houses of two bays, without basements and mostly without attic rooms. (The main exceptions are a few houses with towers or attics, some basement houses in Grayshott Road and the two corner ‘Gothic houses’ in Eversleigh Road). They were designed in four classes, first or ‘clerk’ class having eight rooms: a bay windowed front parlour, a dining room or back parlour, a kitchen, larder and scullery, with three bedrooms and reportedly a bathroom on the first floor.

Few if any bathrooms were actually fitted up, and the only first-class house plan illustrated in the Davis & Emanuel report of 1875 had no bathroom. The upstairs was divided into four bedrooms, two of them very small, and a second WC. The smaller houses nearly all had flat fronts apart from entrance canopies, but a few had bay windows for emphasis at either end of some terraces. Class 2 houses lacked the bathroom or fourth bedroom; so did those of Classes 3 (six rooms) and 4 (five rooms, two of them bedrooms).

Since even the Class 4 houses proved out of the reach of the really poor, Alfred Walton suggested that the company should build ‘a few small cottages on our Estates’ for the ‘lowest class’ – but the idea was not acted upon. The higher-class houses had wider frontages, higher ceilings and a better standard of finish. Davis & Emanuel considered the smaller houses well planned, but criticized the larger ones for their ‘dark and ill-ventilated staircases’. Overall, they did not much differ from the many similarly planned terraced houses of the time.

Inside, the houses were supplied with cupboards, shelves, plate-racks, coppers and kitcheners, window blinds and ‘in fact, with everything which belongs to an ordinary well fitted-up house.’ One report described the best parlour of a first-class house as being fitted with dwarf cupboards, no doubt either side of the fireplace, which had a chimneypiece of enamelled slate.

From a sanitary point of view, the company was right; combined back drainage was already standard in several parts of the country and had many advocates. But Wandsworth District Board of Works was opposed to it (as, apparently, was Bazalgette of the Metropolitan Board). A long-running and costly battle ensued, involving a Chancery suit by the company and a Parliamentary Bill. The issue was only resolved well after the new directorate took over, so intractable was the District Board. (One of the new directors later recalled a meeting at which ‘we were treated as criminals … very roughly used indeed. Ever since then I have been afraid to approach the Wandsworth Board of Works on anything’.)

Part of the original scheme was the planting of lime and plane trees along the roadsides; many of the original trees died and were replaced with planes in 1882. More trees were planted in the late 1890s. The footpaths were originally asphalted, probably because this was seen as the most sanitary surface available; the roads were simply gravelled…

…Rooms were finished with wallpaper and grained and varnished woodwork, and front doors were also grained not painted. A long-time resident recalled that the door numbers, letter-boxes and knockers were all bolted on for easy removal by the decorators. Ventilation, considered vital for reducing disease, was provided throughout, in the walls, over doors and under floors, by flues in the external walls (dismissed by Davis & Emanuel as ‘an entire failure’).

Much modernisation was carried out by the Peabody Trust in the early 1970s and few of the houses can now retain many original fittings…

…The architectural treatment tends towards Gothic, chiefly embodied in the entrance canopies described below, but more fully developed in the few larger houses designed for architectural emphasis. The most important are the two ‘tower houses’ at the estate entrance in Eversleigh and Grayshott Roads, the detached ‘Gothic houses’ in Eversleigh Road, and the turreted houses in Elsley Road. An exception is the former Shaftesbury Terrace on the east side of Tyneham Road, with detailing in red brick and a loosely classical central pediment topped by miniature urns. The wording in the tablet here was changed from Shaftesbury Terrace to Shaftesbury Estate when it was repaired in 1885…

…The estate is seen at its best along Grayshott Road and the eastern part of Elsley Road, where the house-front designs are better resolved and the pointed slate roofs of the turrets give attractive vistas. Turrets are again used to some effect in Eversleigh Road. Elsewhere, notably Sabine Road and Morrison Street, a few gabled attics lit by small lancets are less effective in relieving otherwise uniform terraces.

Nearly all the original houses are of grey or yellow stocks, but the terraces in Tyneham Road between Sabine and Ashbury Roads have red-brick fronts. Red and occasionally black brick was used for decorative effect throughout the estate, for the corbels under the eaves, and in stringcourses, diaperwork, voussoirs to windows and the projecting canopies over the front doors. These canopies, carried on large stepped corbels, are among the estate’s defining features. Some are merely flat-roofed, but in the grander and more overtly Gothic examples, with artificial stone arches, they rise so steeply that the tops reach almost to the eaves.

Though these prominent canopies were applied to the larger houses they are absent from the first-class houses in Grayshott Road, where the coloured brick voussoirs of the windows and porches and the ornamental corbelling are the most striking features. Some of the later Grayshott Road houses, built in 1876 on the intended public hall site between Ashbury and Sabine Roads, and those on the west side of Brassey Square, have recessed Gothic porches with moulded ornament in the pediments, refining the earlier canopy designs.

Much use was made of artificial stone for decorative lintels, sills and colonnettes, though the ubiquitous plaques intricately modelled with the date and company monogram are mostly terracotta.

Some of the artifical stonework was made on site, as was all or most of the joinery. Brick and stone decoration was augmented by cast-iron railings on the front walls and window sills, which were deep enough for displaying pot-plants. Many of the iron pot-guards have survived, but the garden-wall railings were mostly replaced by the company in the 1890s, local boys having discovered how easy it was to knock off the ‘rather prominent’ heads. Some of the originals survive in Grayshott Road.

Pot-plants, creepers and ornamental hedges were all to which the Shaftesbury Park gardener could aspire in the diminutive front plots. One early resident settled for deadly nightshade. The back gardens or yards were more generous (some occupiers finding room for keeping hens), but the overall tightness of the layout was criticized; the Building News would have preferred fewer houses, and some semi-detached pairs instead of terraces.

The yards originally contained brick-built dustbins, emptied at long intervals. These were demolished about 1889 when Battersea acquired a municipal incinerator or dust-destructor, allowing more frequent refuse collection and portable galvanized-iron bins. Sanitary arrangements were not particularly advanced, the original wcs being without flushing cisterns, which all had to be modified or replaced in the 1890s…

…The north building consisted of a hall, called the Masonic Hall, and three shops with living accommodation below, taking up the ground floor and basement. There was some thought of building a large lecture hall in the space between the buildings, but in March 1877 Swindlehurst advised using the site for large houses or, better still, a church or chapel, which would bring in a good ground rent. The scheme came to nothing. Meanwhile the Grayshott Road frontage was built up with comparatively large houses.

The building of the Masonic Hall was doubtless done at the urging of Langley, who was behind the founding of a masonic lodge at Shaftesbury Park; Soloman Frankenberg, the crooked builders’ merchant, was a lodge member. It is said to have been the first purpose-built masonic hall in South London, but was probably never used as such.

Construction was under way when the new board took over in July 1877. Austin survived in post for a while, one of his new tasks being to substitute plain stone chimneypieces in the Masonic Hall for more expensive ones he had designed. The new names Shaftesbury Hall and Shaftesbury Hall Buildings (for the shops) were adopted. The shops were soon let to the Shaftesbury Park Co-operative Society, which failed a few years later. The hall too proved a white elephant. It was used for a time by the Shaftesbury Park Co-operative Literary Institute and for occasional public meetings. George Holyoake lectured there on co-operation. It was given over to a social club, which supported a choral group, dramatic society, library and cricket club.

But the board (which retained the teetotaller and self-help ideals of the founders) was not pleased to learn that the main attraction was billiards and that many members wanted alcohol to be sold. The hall ‘degenerated into a dancing-saloon’, which closed in July 1888, by which time it had been decided to turn the building into flats, subsequently named Shaftesbury Park Chambers. These were completed in 1889, providing 7 two-room and 15 three-room apartments, to designs by the company’s block-dwellings architect F. T. Pilkington. It involved extensive reconstruction, particularly of the upper parts, producing a block of striking incongruity among streets of cottages.

…Ashbury Road is named after James Lloyd Ashbury, the railway-carriage manufacturer and transatlantic yachtsman, a shareholder from 1872. It was originally Derby Road, after the Earl of Derby, a supporter and shareholder, on whose estate at Bootle the company planned to build. Ashbury Road was built up by the end of 1875, except for the houses on the Brassey Square site.

Birley Street (originally Henrietta Street, possibly after Robert Austin’s daughter), of 1875-6, is named after the Manchester MP Hugh Birley, a shareholder who may have been helpful over the Salford development…

…The two detached ‘Gothic houses’ (18 and 42 Eversleigh Road)

occupy triangular plots at the junctions with Kingsley and Ashbury Roads, relieving what might otherwise have been a monotonous vista of two-storey terraces.

They have date-stones similar to those on the terraces throughout the estate, but incorporating the initials of Robert Austin (at No. 18)

and William Swindlehurst (at No. 42),

instead of the company monogram, suggesting that they were intended as their respective residences. Further visual interest is given by turrets with pointed roofs at the ends of the terrace between Grayshott and Ashbury Roads.

The attempt to mix workmen’s cottages with bourgeois villas in this way was ideological as much as artistic, and both houses were slow to let. A doctor’s offer for one in 1877 was turned down because he wanted a guarantee that no other physician would be allowed a tenancy on the estate. By 1881 both were occupied: No. 42 by a commercial clerk and his family, and the larger at No. 18 by three families, two headed by carpenters and the other by an artist, Arthur Austin…

…Grayshott Road. Nos 57-69 are the oldest houses on the estate, begun in 1872. The remainder were built in 1874-6; the two ‘tower houses’ at the south end denoting the estate entrance (now Nos 32 and 45) bear date-stones marked 1874,

while the majority were occupied before the end of 1875…The ‘tower houses’ (Nos 32 and 45) were converted into shops in 1883-4 to plans by Rowland Plumbe, one being run by estate superintendent May, selling sweets, toys, stationery and tobacco…

…Tyneham Road was originally called Elcho Road after the company’s co-arbitrator, the politician Lord Elcho (later 8th Earl of Wemyss and 6th Earl of March). It was early on renamed Tyneham Grove, being a continuation of Tyneham Road to the south, with which it was formally merged in 1881.

The temporary lecture hall built by Jonathan Parsons was pulled down by the new board in 1877 and replaced by seven houses with shops built by the company (now 35-47 Tyneham Road). They appear to have been designed by J. V. Sigvald Muller, on whose recommendation a small hall (known as Tyneham Hall or the Temperance Hall) was included above the two shops on the corner of Elsley Road.”