From Bitch: What does it mean to be female? (2022), by Lucy Cooke:

“…(Alfred) Jost’s theory slotted in nicely with the widespread notion, popularized by Darwin, that females were generally passive and males active. The theory was embellished by others and labelled the Organizational Concept – the universally accepted model for sexual differentiation not just of bodies, but behaviour too. It placed male gonads and androgens in the starring role – the saviours of the sexual paradigm and chief architects of all things male.

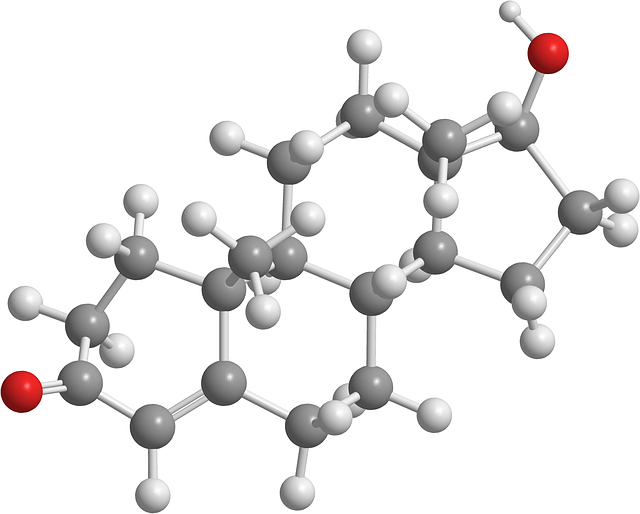

Testes and their testosterone-pumping powers became the engine driving the demarcation of not just the embryonic gonads and genitals, but also the fetal neuroendocrine system and developing brain. This then programmed sexual differences in bodies and behaviour that could be activated by sex steroid hormones in later life. Thus testosterone became the executive director of sexual dimorphism; responsible for characteristics ranging from the hefty horns on the stag to the bull elephant’s raging musth and the male walrus’s fearsome size and temper.

Jost’s findings revolutionized the ongoing debates in endocrinology on the hormonal origins of masculinity and femininity. At a conference in 1969, Jost explained: ‘Becoming a male is a prolonged, uneasy and risky adventure; it is a kind of struggle against inherent trends toward femaleness.’

The masculine journey was seen as a heroic quest worthy of investigation. In contrast, the now-famous French embryologist referred to females simply as the ‘neutral’ or ‘anhormonal’ sex type…

…This bias in our understanding comes from Jost’s famous but flawed theory of sex differentiation, which only ever explained how you differentiate a male and never questioned how the female is created. The idea that any development process could be ‘passive’ is clearly quite ludicrous – ovaries require just as much active assembly as do testes. Yet for fifty years the ‘default’ female system went unstudied.

‘Sexual differentiation isn’t about describing how you get females and males. It’s only about describing how you get males. For decades people were happy not to have an explanation of how you get the female form and just saying, “Well, it’s passive,”’ (Christine) Drea asserted.

A foundational publication on mammalian sexual development from 2007 referred to the development of the ovary as ‘Terra Incognita’. The prevailing view that ovarian development is the ‘default’ state had, it claimed, led to ‘a widespread understanding that no active genetic steps need to be taken to specify or create an ovary or female genitalia’. Which, the authors wryly note, is ‘a rather amazing situation given the importance of this organ for proper female development and reproduction’.

Things are improving. The unknown land of ovarian development has now been partially explored, but its genetic map is far emptier than the one that exists for testes. The *chauvinistic hangover of the Organizational Concept has focused the genetic quest for sexual determination firmly on the male; at its core was the hunt to find the elusive testis-determining factor, the genetic trigger that instructs those neutral fetal gonadal cells to rouse themselves out of their sexually indifferent slumber and transform into testes (and start pumping out testosterone).

The genetic recipe that actually determines the sexes is, however, positively **byzantine in nature and features an ancient cast of surprisingly androgynous genes…”

* “chauvinism (n.)

1840, “exaggerated, blind nationalism; patriotism degenerated into a vice,” from French chauvinisme (1839), from the character Nicholas Chauvin, soldier of Napoleon’s Grand Armee, who idolized Napoleon and the Empire long after it was history, in the Cogniards’ popular 1831 vaudeville “La Cocarde Tricolore.” The meaning was extended to “excessive belief in the superiority of one’s race” in late 19c. in communist jargon, and to (male) “sexism” in late 1960s via male chauvinist (q.v.).

The surname is a French form of Latin Calvinus and thus Calvinism and chauvinism are, etymologically, twins. The name was a common one in Napoleon’s army, and if there was a real person at the base of the character in the play, he has not been certainly identified by etymologists, though memoirs of Waterloo (one published in Paris in 1822) mention “one of our principal piqueurs, named Chauvin, who had returned with Napoleon from Elba,” which action implies the sort of loyalty displayed by the theatrical character.

**Byzantine (adj.)

pertaining to Byzantium (q.v., original name of Constantinople, modern Istanbul), 1770, from Late Latin Byzantinus; originally used of the style of art and architecture developed there 4c.-5c. C.E.; later in reference to the complex, devious, and intriguing character of the royal court of Constantinople (1937). As a noun from 1770. Byzantian is from 1610s.

ancient Greek settlement in Thrace on the European side of the Bosphorus, said to be named for its 7c. B.C.E. founder, Byzas of Megara. A place of little consequence until 330 C.E., when Constantine the Great re-founded it and made it his capital (see Constantinople).” (Online Etymology Dictionary)